Filed under: General Health, Nutrition

I recently had a comment from a reader on one of my recent posts on cancer prevention asking this:

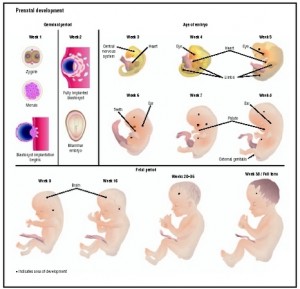

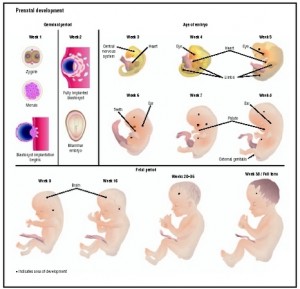

“On the topic of exposure to harmful chemicals/substances etc, – have you ever written on prenatal nutrition for those who are looking to have children? Also, what to do to minimize exposure to harmful substances while pregnant? Perhaps some general guidelines for healthy eating during pregnancy? I think that would be an interesting topic.”

While I don’t think this topic can be sufficiently covered by a blog post I am certainly happy to provide some general guidelines for healthy eating during pregnancy. I will also point out that my good friend and colleague Cassandra Forsythe has written extensively about nutrition and training during pregnancy on her site, and I highly recommend you check that out if this is something you are truly interested in learning a lot about.

To start I don’t think the general principles of good nutrition change all that much during pregnancy besides the fact that many women find it difficult to smell or consume a lot of foods they normally like in the first trimester (and sometimes throughout the entire pregnancy). This particular issue can be a challenge, but do realize that it is mostly temporary. For example my wife really struggled to keep food down and was simply not interested in eggs and other meals we used to eat on a regular basis. For a while she was really relying on cereal with some cold milk (full-fat, grass-fed of course) because it was simply all she could keep down. After a few weeks she was able to slowly get back to “normal” eating so it really wasn’t a big deal. Again, it is just important to remember that this stage is usually temporary. If it persists you should certainly discuss this with your doctor or midwife.

Having said that, some of my simple tips would be as follows.

Read the rest of this entry »

Filed under: Nutrition, Training

I recently had the fortune of interviewing the bright and talented Kevin Neeld on his new training manual – Ultimate Hockey Training. Kevin is a good friend of mine and was an early CP intern back when I was a new CP employee. He was the first intern we ever had who could have been hired as a coach before he even started interning, he was that good. And he has only gotten better.

Well, without further ado, enjoy the interview!

BSP: Kevin, first off why don’t you tell us a little about yourself – school, athletic career, training career, how you look up to me? You know, the basics.

In the interest of getting the boring stuff out of the way, I did my undergrad work in Health Behavior Science with a minor in Strength and Conditioning at the University of Delaware, and later got my Master’s in Kinesiology with a concentration in Exercise Neuroscience at UMass Amherst. Say what you want, but people that study neuroscience are cool.

I grew up playing ice hockey, and would objectively say that I had pretty good skill sets that I was too fat, slow, and generally unathletic to express at high levels. Luckily, I had an older brother to constantly remind me of these things, so I was never at a loss for motivation. This was what originally got me into training. It had a profound effect on my performance, and I knew at around the ripe age of 14 that I would ultimately build a career that revolved around helping athletes fulfill their potential through effective training. What I didn’t know then, is that the training that “worked” so well, was also completely moronic and lead me down a fun path of injuries that included a broken collar bone (in two places), inguinal hernia (and subsequent surgery), torn trapezius off the posterior clavicle, separated AC joint, hamstring strains, long-term “groin” pain, and periodic knee problems, all of which affected my hockey career to some extent. Oh, and I’m not very tall…which sucks.

BSP: As a former hockey player myself, I am well aware of the poor training we are given – hours and hours of “dryland” anyone? I am also especially aware of the poor diets of most young athletes, and guys playing junior hockey in particular. Your new book, Ultimate Hockey Training, fortunately rights this ship and provides players with appropriate training and nutrition programs. What I want to know is what in particular prompted you to focus that big brain of yours on hockey in the first place?

As I mentioned, I played hockey almost exclusively growing up. I would say my appreciation for the sport wavered somewhere between a determined commitment and an unhealthy obsession. I loved the game. I still do. Hockey has always been my passion. What most in the strength and conditioning field don’t know is that I have a good amount of experience running on-ice skill work as well. I came to a cross-roads in my career between diving into either the on-ice or off-ice development route. My decision led me to pass up an opportunity to run my own series of off-season on-ice development clinics in favor of paying out of pocket for a Functional Anatomy class that was part of Boston University’s DPT program, and interning at Cressey Performance. Other than having nightmares of having to lift to Disturbed over and over and over (thanks Eric), I would say that experience was universally positive and has probably been the smartest move I’ve made in my career.

I’m realizing now, that I was accidentally very fortunate to have chosen to build a career around training hockey players. In my experience, hockey players are passionate, hard working and attentive athletes, meaning they’re proactive in their development and willing to try new things if they understand how it will benefit them. This is true of some athletes in all sports, but as a whole, hockey players seem to be the most consistent in these qualities.

BSP: As the Director of Athletic Development at Endeavor Sports Performance, one of the premier hockey training facilities in the country (located in Pitman, NJ, FYI), what are some of the most common issues you see among young and old hockey players alike? Essentially what are the problem areas related to hockey that people need to work on or be aware of, regardless of skill or playing level?

As you know, I could write a whole book addressing these issues (shameless plug for Ultimate Hockey Training). The reality is that there are a number of hockey- and individual-specific things that warrant special attention, and it’s hard to make generalizations based simply on the demands of the game. For example, a person that has an excessively pronated (read: flat) left foot or forward head posture will need to have these issues attended to, regardless of what sport they play. I think people sometimes forget that a lot of sport injuries have lifestyle-driven mechanisms or predispositions. In other words, it’s the postures and movements (or lackthereof) AWAY from sport that brings many injuries closer to threshold. I could go on, but I have a feeling that this discussion would be like Nyquil for your readers coming from a hockey background.

I generally think of training as serving two primary, but HIGHLY integrated purposes: improving performance, and preventing injuries. In the interest of both, we need to make sure the athlete is structurally ready to improve performance measures. This comes down to assessing for postural and functional asymmetries, which I’ll talk more about later, but generally hockey players have extreme cases of adaptations-related to sitting too much. They’re tight in the front of their hips, hyperextended through their lower backs, rounded forward through their shoulders, etc. This, amongst other things, is what leads to the exceptionally high prevalence of hip flexor and adductor strains we see in the sport and, in my opinion, is a huge factor in the concussion epidemic that is infecting high level hockey currently. If you only look at a brain, you’re missing the big picture

Looking at training through a purely hockey perspective, the sport demands extremes in transitional speed, rotary power, anaerobic lactate conditioning, and collision resistance. That said, there are appropriate training progressions to maximize these abilities and if you only take them at face value and build a program around strictly these qualities, you may do more harm than good. For players with a “young” training age, everything will seemingly work. This means that every stupid, insane, scientifically unfounded, and completely moronic training technique ever created will lead to what appears to be an improvement in performances. Much of these training tactics are either proposed from naïve or downright ignorant people (many of whom have very positive intentions!), or someone selling something, and they all fail to look at the long-term perspective of development. Improving your vertical jump height doesn’t matter if your knees buckle on the load and land! Improved performance? Not in my eyes, but when you’re presenting numbers to a 14 year-old’s dad, they’re hooked. This is just one example; I could draw parallels to EVERY athletic quality that are equally misguided and short-sighted.

To be honest, these are problems that affect all youth sports, not just hockey. In the U.S. we do everything we can to rush development, even in the face of a ridiculous amount of evidence demonstrating that the most effective way to produce WORLD-CLASS athletes is to follow slow, focused progressions. In other words, we need to slow roast our athletes, not toast them. In hockey, it’s interesting to see that the U.S. has won the Gold Medal at the IIHF World U-18 Championships the last three years (‘09-’11), while at the U-20 level, they didn’t medal at all in ’09, won Gold in ’10, and Bronze in ’11, and at the Men’s level didn’t medal in any year. Do you notice a trend? Our development system leads to rapidly developed players at young ages that fail to progress beyond that point. Because we don’t create a large enough foundation, we lose the ability to progress to peak heights. We’re winning the race to the wrong finish line.

USA Hockey has done an outstanding job in rewriting our developmental programs to help right the ship. I think people hear of how the Soviets identify high performers at young ages and think that’s the way to go. Pick them early, and then drill them with single-sport development. What they don’t realize is that these “single-sport focus” schools MANDATED that kids play multiple sports up to a certain age! This means that at “hockey school”, you would spend a significant portion of the year playing soccer, tennis, etc. A broad base of athletic motor qualities is what leads to future elite level performance. USA Hockey gets it, and they’ve put together a terrific package in their new American Development Model for coaches to use. The problem is that many coaches are flat-out too stubborn to adopt these HIGHLY researched principles. It’s amazing how people with so little information have such strong opinions on these issues.

I’m not even sure I answered your question, but you got me all fired up!

BSP: Let’s discuss a little bit about program design. When assessing a new athlete, what are some things you’re looking at? Are there any exercises in particular that you try to avoid with your hockey athletes? Are there any exercises that you try to incorporate often?

Our protocol for hockey players uses a combination of assessments taken from Functional Movement Systems, the Postural Restoration Institute (PRI), and traditional orthopedic measures. We put a lot of focus on determining the structural make-up of their hips, as, in my opinion, problems such as hip flexor and groin strains, femoroacetabular impingement, labral tears, sports hernias, and SI joint dysfunction have gotten completely out of hand in the hockey population. All of these issues are multi-factorial, but prevention starts with getting an understanding of where the athlete is structurally and making program and technique adjustments to allow them to be successful with their structural make-up. I met a guy at a seminar over the Summer that was completely blown away that I could asses for ante- and retro-version of the hips without using fancy and expensive imaging techniques. It’s possible, and it’s also possible to dissociate between femoral adaptations and those more specific to the positioning of the acetablum. As Eric used to say, it’s not rocket science because we aren’t building rockets!

The PRI information has been a revolutionary addition to how we handle our hockey players. Most players lack left hip adduction and are stuck in a relative position of external rotation, which leads to a number of compensations. Most notably, it means:

- Anytime they crossover to the left, they’ll be putting excessive strain on their left abdominal wall

- Anytime they stride with their left leg, there are opportunities for compensatory movement of the SI joint on either side

- They’re likely to develop laxity of their left anterior hip capsule

- They’ll feel more comfortable crossing over to the right than the left

There are a couple exercises we avoid with just about everyone, but most of the adaptations in exercise selection come down to how the individual player presents. An athlete with CAM impingement will not be pulling from the floor or squatting past parallel, at least not unless their primary training goal is to shred their labrum (haven’t had this one yet). We tend to emphasize unilateral and dissociated limb exercises in addition to traditional bilateral movements to capitalize on the neural circuitry and increased degrees of freedom associated with these movements.

I also think it’s worth noting that the adductor complex needs to be trained under eccentric loads. This isn’t necessarily something you should jump right into, but it’s definitely a goal to progress to. These stresses should stem from both closed- and open-chain movements to help prepare the player for the stresses of high velocity skating.

BSP: Ok, let’s get to the nitty-gritty of it all. Tell us a little about Ultimate Hockey Training – specifically that incredible Nutrition Guide that someone awesome wrote to go along with it. I’m kidding, sort of. Seriously though, it is an incredible and comprehensive resource for hockey players of all levels, but what distinguishes this from any other similar product out there?

I wrote Ultimate Hockey Training to be the most comprehensive resource on the subject ever written. I wanted to give a presentation of EXACTLY how we approach training hockey players at Endeavor. UHT discusses age-appropriate guidelines, year-round training recommendations, training strategies for improvements in every major athletic quality, the most in-depth look at exercise progressions and regressions I’ve ever personally seen, and has special topics pertaining to specific hockey injuries. In an era when crafty marketing is used to sell 12-week generic one-size-fits-all programs, I wanted to provide hockey players, parents, coaches, and S&C professionals with a resource that provides the philosophy AND methodology on how to train smart through an entire career, not a couple phases of one year. It’s the old “give a man fish, feed him for a day; teach a man to fish, feed him for a lifetime” idea. The feedback that I’ve gotten over the last month has been extremely positive.

To pump your tires a bit, as proud as I am about Ultimate Hockey Training, I think Ultimate Hockey Nutrition (which is exclusively available to people that purchase the book) is really the icing on the cake. I still remember when you and I first spoke about the idea for UHN about 12 years ago, and you said, “I’ll have it done in a week.” Well, it didn’t exactly unfold that way, but it was well worth the wait! The goal was to answer all of the most common questions how players, parents, and coaches have about their nutrition:

- What should I eat before games?

- What should I eat after games?

- What should I eat during tournaments?

- What should I eat if I have to eat out?

- What should I eat to gain muscle?

- What should I eat to lose fat?

- What should I eat to have arms like Tony Gentilcore?

Because UHN answers all of these questions (well, except maybe the last one), and includes sample meal plans for players at different levels for practices, home and road games, and tournaments, it really is the single-most comprehensive AND applicable nutrition resource that’s ever been created for hockey players. And honestly, the full package couldn’t be any more affordable. You and I were both on the same page when we said, “we want to make this available for EVERY single person in the hockey community.” The most important thing to me (and to you) is that the information gets out to everyone. I’ve always said that I’m a terrible businessman, and I think this proves it!

BSP: Kevin, thanks for taking the time to provide my readers which such a thorough and thought provoking interview!

Thanks for having me!

Filed under: General Health, Nutrition, Training

Keeping in the same vein that of my previous two posts (My Family Health Portrait and President’s Cancer Panel Report) is another interesting tidbit I learned in my outpatient rotation at the Cancer Center – The World Cancer Research Fund and American Institute for Cancer Research joint report - Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity and the Prevention of Cancer: A Global Perspective.

This report is a compilation of ALL of the data gathered so far about how food, nutrition and physical activity impact our risk for cancer. They show how fruit consumption has probable evidence for decreasing the risk or oral, esophageal, lung and stomach cancer (among others), while something like breastfeeding has convincing evidence for decreasing risk of breast cancer in pre and post menopausal women.

If you don’t want to read through the entire report they do provide a nice summary of the research right HERE.

Now I will say that much of this research is epidemiological, simply because that is an easy way to study a lot of people and find associations, however it does not prove causality. In addition the research is far from complete. You may wonder why certain foods have so few associations, and that may also be because they have not been studied with each type of cancer outlined.

Regardless it is a handy compilation of the data and a simple reminder to exercise plenty, maintain a healthy body weight and body composition, and eat a diet based on real, whole, minimally processed food.

Posted on December 30th, 2011 by Brian St. Pierre

8 Comments »